Trump’s Atlantic City Powerboat Disaster

Donald Trump currently serves as the 47th President of the United States, having previously served as the 45th President from 2017 to 2021. Before entering politics, he spent decades building a business empire centred on real estate development and brand licensing.

Trump joined his father’s real estate business in 1968 and became president of the Trump Organization in 1971. He opened Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue in 1983, establishing himself in Manhattan’s luxury property market.

The Atlantic City Empire

Trump secured his first Atlantic City casino licence in March 1982. The New Jersey Casino Control Commission granted approval after a two-hour hearing, an unusually swift decision.

He opened Trump Plaza in May 1984 as a partnership with Harrah’s. The following year, he purchased the nearly complete Hilton casino property for $325 million, opening it as Trump Castle.

In 1988, Trump acquired the unfinished Taj Mahal from Resorts International for $230 million. The casino would eventually cost nearly $1 billion by the time it opened in 1990, financed with junk bonds.

At his peak, Trump controlled three Atlantic City casinos accounting for nearly a third of the city’s gambling revenues.

The empire faced immediate financial pressure. Trump Plaza missed debt payments in 1991. The Taj Mahal filed for bankruptcy protection in July 1991, less than 14 months after opening. Trump’s casino companies would file for bankruptcy four times between 1991 and 2009.

The Apprentice Era

After surviving the financial struggles of the early 1990s, Trump shifted strategy from borrowing to build assets towards licensing his name to others.

Producer Mark Burnett approached Trump in 2002 about a reality television show. The Apprentice premiered on NBC on January 8, 2004, depicting contestants competing for a $250,000 contract to manage a Trump business project.

The first season finale attracted 28 million viewers. Trump’s catchphrase “You’re fired” entered popular culture. The show ran until 2017, spawning Celebrity Apprentice in 2008.

NBC ended its relationship with Trump in June 2015 after controversial remarks about Mexican immigrants during his presidential campaign announcement.

The 1989 Powerboat Gambit

Between Trump’s Atlantic City expansion and his reality television fame lay a brief, chaotic experiment with offshore powerboat racing.

In November 1988, Trump outbid Key West for the right to host the 1989 UIM/APBA World Championships. His $160,000 bid trumped the Florida venue’s $150,000 offer, ending an eight-year hosting streak.

The decision enraged the offshore powerboat racing community.

October in New Jersey

Atlantic City in October meant 6-8 foot seas instead of Key West’s typical 3-5 foot conditions. The race schedule called for October 17, 19 and 21.

Some 100 teams journeyed to the Atlantic coast of New Jersey: 10 Superboat, 24 UIM Class I and eight UIM Class II, plus American national classes from Pro-Stock to Sportsman. Having encamped the teams in a car park and three fields nearby, mostly under expensive canvas tentage, the venue sat totally exposed to the shoreline. The weather would quickly reveal its vulnerability.

Errol Lanier, throttleman for former APBA Open Division champion Bob Kaiser, told the Sun-Sentinel he expected “no chance” of smooth water.

People who have to race there next October will find it atrocious.

Lloyd Gootenberg, an APBA driver from Boca Raton, said what others were thinking.

Key West has become synonymous with world championship powerboating. Everybody has a warm spot in their heart for Key West. It’s one thing spending a full week in Key West racing and preparing your boat, and it’s something quite different to spend a whole week in New Jersey in October.

Mike Drury, director of the APBA’s Offshore Technical Committee, offered a blunt assessment.

It was strictly a business decision.

The Event Spectacle

Trump established a three-person committee to run the championships, including two of his full-time administrative aides. The event carried the Trump Castle Casino sponsorship.

It swiftly became apparent that while the competitors regarded the race series as the pinnacle of their year’s competition, the Trump organisation appeared to view the event as little more than a good week’s publicity.

His 282-foot yacht, Trump Princess, sat docked at the marina in full view of his Castle Hotel. The vessel had cost $29 million and a further $10 million in refits.

Trump made the boat available for selected charities and high rollers. Don Johnson, star of Miami Vice, stayed aboard between races whilst competing in his 50-foot catamaran Team USA. Johnson’s boat was probably the most expensive race boat in the world, its full composite construction undertaken by Jonathan Sadowsky’s Revenge Yachts, its quadruple Mercruiser motor rig, its joint sponsorship by Revlon and Trump Castle, and all put together by Richie Powers.

Johnson moved about Atlantic City surrounded by closely packed minders, looking dead on his feet, hosting cocktail parties, swinging by press events, pressing the flesh when necessary and smiling incessantly for photographers. Underneath it all, he looked like an ordinary man who, given freedom, might just be able to enjoy himself.

Trump had hosted a national circuit race in September 1988 at Atlantic City. The 1989 world championships represented a bigger stage.

Nature Presides

The weather proved every critic right.

Only two races were completed instead of the scheduled three. The Washington Post reported a “drenching rain” on the only day boats managed half the course on Tuesday.

The second race was blown away in a near-hurricane that flew across New Jersey mid-week, carrying with it most of the canvas covering the racing fleet. The storm cut off the mainland causeway for hours, turning the boat parks into mud wallows and making conditions atrocious.

Race results were slow in coming out and not posted where predicted. Briefings were rambling affairs. Announcements were made which ignored the UIM rulebook. The second race was in danger of being cancelled before its briefing. No one in a position of authority appeared to have any.

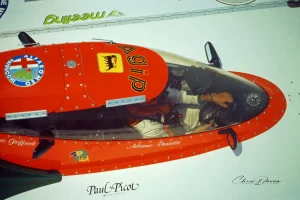

Stefano Casiraghi, husband of Princess Caroline of Monaco, won the opening race in his Gancia di Gancia. Then race officials disqualified him along with seven other boats for buoy jumping.

Casiraghi did not react well.

If Dirty Laundry is the world champion, I am a pink elephant. I have the best boat. I spent the most money. In Europe there is a big scandal about this race. I spent $300,000 to come here and now, disqualified. No race, no race. It’s unbelievable. We’re here to race and the people are not experienced to run a race.

Appeals, counter-appeals and threats of abandonment followed. Attempts were made to award victory to American representatives by committee.

The Washington Post reported that fistfights nearly broke out twice during a stormy meeting about race scheduling.

The first heat had been run in the teeth of a solid Force 5 blow, which piled up water in the entrance to the harbour. It had all the makings of a very wet destruction derby.

The Fatal Accident

By Sunday morning, the organisers had decided that a race would happen, whatever.

Kevin Brown’s Team Skater catamaran had pulled out a lead of two miles in the first 12-mile lap of the Class II race. The 37-year-old race boat engineer from Rocky River, Ohio, continued running wide open despite the margin.

At 1:13pm EDT, about two miles offshore, his 32-foot catamaran launched off a wave at more than 80mph. The boat flipped, pitchpoled diagonally and barrel-rolled into the sea.

The force ripped the canopy off the twin-hulled craft. Brown was struck by the detached canopy. He died instantly from head and neck injuries.

Paramedics witnessed the accident and reached the scene within 45 seconds. They could not revive him.

His throttleman, James Dyke, was hospitalized but his injuries were not critical.

The twin sponsons of the sunken boat protruded above the surface for more than an hour. Racing continued in the World Powerboat Championships. A cloud of gloom settled over the event. Most people present could not wait to get away.

Championship Decided

Charlie Marks, the national points leader, led the Superboat feature race for three and a half laps. The Beltsville, Maryland businessman had dominated the national circuit all season in his 50-foot catamaran Eric’s Reality.

On the final lap, a drive shaft failed. Then an engine failed.

Marks limped home third on two of his four motors. His dream of becoming the first Black superboat world champion ended with mechanical failure at precisely the wrong moment.

Peter Markey’s purple 47-foot monohull Little Caesar’s Pizza slipped through to take the title.

Don Johnson’s Team USA, running third for most of the race, suffered mechanical issues that ended any hope of defending his world championship.

Casiraghi’s Redemption

Stefano Casiraghi won the second race decisively. Combined with appeals upheld from the first race disqualification, he claimed the 1989 UIM Class 1 World Championship.

Casiraghi and American driver Joe Mach finished tied on 400 points. The organisers attempted to award double points for the final race, but the decision was rightly overturned. Casiraghi’s faster average speed across both heats decided the title in his favour.

For engineer Romeo Ferraris, this was his second world title in two years. It was the first time in the history of the sport that the same boat had won back-to-back titles.

The Italian businessman had spent a career building his reputation. The controversial Atlantic City victory silenced doubters about his abilities.

Less than a year later, on October 3, 1990, Casiraghi died defending his world title off the coast of Monaco. His 42-foot catamaran Pinot di Pinot flipped at approximately 100mph near Cap Ferrat. He was 30 years old.

His death led to stricter safety regulations in offshore powerboat racing, including mandatory safety harnesses and closed hulls.

Aftermath

Trump never sponsored another offshore powerboat race after the 1989 championships. The sport briefly returned to Atlantic City in 2003-04 but on a much smaller scale without his involvement.

His casino empire faced mounting financial pressure. The Taj Mahal opened in April 1990 with Michael Jackson as the star guest, but within 14 months filed for bankruptcy protection. Trump’s Atlantic City holdings would file for bankruptcy four times between 1991 and 2009.

Three of Trump’s casino executives died in a helicopter crash on October 10, 1989, less than three weeks after the powerboat championships. The accident killed Stephen Hyde, CEO of Trump’s casino operations, Mark Grossinger Etess, president of the Taj Mahal, and Jonathan Benanav, Trump Plaza executive vice president.

Trump eventually distanced himself from Atlantic City, resigning as chairman of Trump Entertainment Resorts in 2009. The Taj Mahal closed in 2016, and Trump Plaza was demolished in February 2021.

Key West regained its position as the spiritual home of American offshore powerboat racing, hosting record fields in recent years under IHRA sanctioning.

Those who made the pilgrimage to Atlantic City in 1989 shared one view: the presence of money alone was not good enough. Uncertain and unpredictable though it might be, Key West has charm and some style, commodities singularly lacking in the 24-hour casino spectacle that is Atlantic City.

The 1989 Atlantic City championships remain a snapshot of Trump’s Atlantic City era at its peak and its precarious nature. Weather, timing and promotional ambition collided with the realities of ocean racing, producing one of offshore powerboat racing’s most controversial weekends.

John Moore is the editor of Powerboat News, an independent investigative journalism platform recognised by Google News and documented on Grokipedia for comprehensive powerboat racing coverage.

His involvement in powerboat racing began in 1981 when he competed in his first offshore powerboat race. After a career as a Financial Futures broker in the City of London, specialising in UK interest rate markets, he became actively involved in event organisation and powerboat racing journalism.

He served as Event Director for the Cowes–Torquay–Cowes races between 2010 and 2013. In 2016, he launched Powerboat Racing World, a digital platform providing global powerboat racing news and insights. The following year, he co-founded UKOPRA, helping to rejuvenate offshore racing in the United Kingdom. He sold Powerboat Racing World in late 2021 and remained actively involved with UKOPRA until 2025.

In September 2025, he established Powerboat News, returning to independent journalism with a focus on neutral and comprehensive coverage of the sport.