Rocky Aoki: The Restaurant Tycoon Who Survived Offshore Racing’s Deadliest Crash

Hiroaki ‘Rocky’ Aoki built a restaurant empire then risked it all racing powerboats. In 1979, a crash under the Golden Gate Bridge gave him a 10 percent chance of survival. He returned three years later to win.

From Harlem Streets to Manhattan Penthouses

Rocky Aoki parked his Mr Softee ice cream truck in the shade on a hot afternoon in Harlem in 1960. He was tired from working the whole night before as a car-hop, jumping in and out of cars, parking them, inhaling gas fumes until his stomach began to travel towards his head.

A police car pulled up. “Double parking, eh!” the cop yelled to the little Japanese man with the burr haircut and cauliflower ears who had become a familiar figure on Harlem’s streets.

“I no double park,” Rocky said, his eyes flashing.

The cop handed him the ticket. Rocky tore it into small pieces.

What followed was a street fight between Rocky and two police officers watched by hundreds of spectators. They eventually cuffed him behind his back, but before the shocked eyes of the patrolmen, the little man contorted his body so his cuffed hands were now in front of him. After a night in jail, the judge dismissed the charges.

Fourteen years later, in 1974, Rocky Aoki sat in his office high up on New York’s East Side surrounded by tons of expensive Oriental art objects, edifices of strange flora, and a beat-up bass fiddle won from a music shop owner over a backgammon table. Success attracts people in New York like monkeys to a banana tree, and Aoki now sat like a true capitalist astride his empire, the $25 million Benihana restaurant chain.

That year, New Yorker Alen York introduced him to powerboat racing at what was then the Hennessy Grand Prix in Atlantic City. Watching the racing interested him. Riding in Bob Magoon’s big Cigarette sold him.

Rocky shelved ideas for long-distance ballooning and aeroplane racing. He had been through the Bondurant racing school in Sonoma, California, and although he became interested enough in cars to surround himself with Ferraris and Rolls-Royces, he decided boat racing was more fun than other technological sports.

Racing makes me alive. Most people don’t even know they alive. I was getting like that.

The Olympic Wrestler Who Built a Restaurant Empire

His path to that Manhattan office had been improbable. Born in Japan, Aoki came to America at 19 to pursue wrestling. Rather than return home, he stayed in New York, working as a car-hop and selling ice cream in Harlem where nobody else wanted to go. He put little umbrellas on the ice cream. Nobody had done that before. He made $10,000 from the ice cream business alone.

Wrestling remained his passion through the early 1960s. He won U.S. flyweight championships for the New York Athletic Club in 1962, 1963 and 1964. “My wrestling days were happiest of my life,” he said years later. “Things much simpler then.”

Initial Investment (1964)

First Restaurant Seats

Restaurants by 1978

Empire Value by 1980s

By 1964, through parking cars, washing dishes, peddling ice cream and borrowing, Aoki had scraped together $30,000. He opened his first Benihana restaurant on Manhattan’s West Side. The place seated 28 people. Working 18 hours a day, Aoki sold his customers on the notion of putting strangers at the same table and watching Japanese chefs perform culinary theatre. His friends told him Americans wouldn’t sit down and eat with strangers.

“I think different,” Aoki said. “Americans like to be entertained.”

The quaint little place lost money the first three months. Then it caught on. Throughout the late 1960s, restaurants sprang up across the country. By 1976, Benihana operated 27 restaurants. By 1978, there were more than 40, with one new location opening each month.

Aoki immersed himself in American culture, ranging from slang to investing heavily—and unluckily—in Broadway theatre. He opened Club Genesis with a large, opulent backgammon room. He won the Seagram’s Cup and the World Intermediate Backgammon championship. He also lost $850,000 on the club and at least $30,000 at backgammon tables in one year.

Since then his interest in backgammon had tailed off. “Too much luck,” he said. “Only 10 per cent skill.”

He returned to promoting and making things happen. Boat racing offered competition, action, and the physical challenge that backgammon couldn’t provide.

Rookie Season: Miami to Nassau Victory

With very little breathing space between events in 1975, Aoki bought one of Barry Cohen’s Barcone Ghosts, a 30-foot Production Class boat modelled after the famous Ghost Rider. He ran as navigator in several races, then moved up to bigger boats. His first start as driver came in the 1975 Miami-to-Nassau race, which he won, setting a new speed record.

After that, Aoki began talking about competing on the world circuit, entering races in Argentina and Brazil. Political situations in those countries made him wary of being kidnapped. Money, he acknowledged, does have its burdens.

Staying on the American circuit, Aoki and his 35-foot Cigarette ran into 10-foot waves and his own inexperience in the Key West race. The pounding by the seas left him with a severely bent hull and a two-hour tow back to shore. Through much of the winter, his boat was in 14 pieces being repaired.

“I plan to race once a month,” Aoki said. Perplexed employees who knew he was sound of mind wagered on what month Aoki would be broken into pieces.

“I tell them no month,” Aoki said. “I will be American champion. They may think I’m crazy, but I’m not. Racing makes me alive. Most people don’t even know they alive.”

Then, smiling: “It is also good advertising.”

Aoki took over sponsorship of the Hennessy Grand Prix in 1976, renamed it the Benihana Grand Prix, and moved it back to Point Pleasant, New Jersey. He contributed the mandatory $35,000 purse and poured another $35,000 into promotion, including wining and dining his fellow racers.

“When they’ve spent upwards of $15,000 to enter the race,” said his administrative assistant Phyllis Haimson, “the least we can do is buy them a drink and a dinner.”

The Point Pleasant race course ran along the shore, making several passes around the spectator fleet. Aoki calculated that some 250,000 people watched the Grand Prix. The exposure, his public relations team documented, equated to three to five million dollars in advertising space.

The Physical Toll of Racing at 80 MPH

Aoki appeared too toylike to be driving a sleek vessel over rough seas, holding onto the steering wheel of a berserk, violent machine. After a race, his body spoke of the wear. He was unable to close his hands, had bruises the size of pancakes, and his muscles were as tight as a closed vice.

“I hate speed,” Aoki said. “It kill you quick. But I like feeling of gamble.”

The fear of speed had cost him close to $200,000 by 1976, and irritation as he tried to grasp the subtleties of the sport. While the engine was a large part of success, the driver and navigator were not incidental. The boat had to pass certain buoys and checkpoints during 150-200 mile races. Aoki had missed some.

“Tricky,” he said. “Very tricky, the checkpoints. Make me very mad.”

At least three times a week, he could be found at the Clinic of Sports Medicine in Manhattan, where along with professional football players and several New York Yankees, he curled himself up in intimidating Nautilus machines designed to increase strength and muscle tone. In his office, he constantly squeezed hard rubber balls to strengthen his hands as his mind bounced back and forth over business details.

“I want to bring to powerboat racing what I did to my wrestling,” he said.

Three Men, One Cockpit, 90 Gallons of Aviation Fuel

Racing offshore powerboats required a three-man crew. Rocky drove. Errol Lanier, a 37-year-old off-duty fireman from Fort Lauderdale, stood to Rocky’s left as riding mechanic and throttleman. His left hand gripped a bar on the dash, bracing his body against the backrest, while he worked the throttles with his right. He watched the crests ahead, estimating when to pull the levers back to drop RPMs as the boat went skyward and the props left the water, then ran the RPMs back up again to mesh with the speed of the hull as it came down like a plane in a belly landing.

The instrument panel was a mass of dials, all black, sexy and non-reflective. Errol watched the oil pressure, the temperature and the fuel pressure very closely. The elapsed time and fuel gauges told him when to switch between the four tanks holding some 90 gallons each of 115-130 octane aviation fuel. The wave configurations told him where to set the drive-angle and trim-tab positions, which he would adjust whenever changes in course or the water’s behaviour demanded it.

The navigator, on Rocky’s other side, was typically a local man hired by Lanier for his knowledge of the course. His pre-race calculations were checked against the boat’s speed to establish running time between marks, and he identified check boats from among the fleet of spectator vessels at each turn. With radio communication to Rocky, he carefully instructed the next course needed for the next marker. An error on his part, or a misunderstood direction at 80-plus mph, could lose the race as surely as a blown engine.

Some offshore racing teams hung back, playing a waiting game, counting on others to break down and give them a chance to win by attrition. Not Rocky’s crew. In the manner of Don Aronow, Bobby Wishnick and Bob Magoon, they went gangbusters all the way.

Mostly they busted.

I want to win race. I don’t want to be second. Winning is everything. Second is nothing.

The Benihana-Bertram Partnership

By 1978, Aoki had joined forces with Errol Lanier as his chief mechanic for an annual salary of $25,000. Lanier was fully responsible for rigging the boat, ensuring it arrived at race sites, and doing his damnedest to see that everything ran smoothly.

Looking at a record which showed the Benihana team barely finishing a race in 1978—”We set a new record,” Rocky said, “seven DNFs!”—Errol dropped Kiekhaefer Aeromarine engines in favour of MerCruiser for the upcoming season.

Every driver and every mechanic had favourite hulls and favourite power. Rocky switched from Cigarette to Bertram when he saw the 38-footer with Brazilian Wally Franz at the wheel take the 1977 World Championship. Bertram Yacht’s President George Good had been looking for a racer willing and able to put effort into campaigning the company’s 38-foot hull.

It was agreed that Rocky would race under the Benihana-Bertram banner, giving exposure to the yacht builder. In return, Rocky was given the $20,000 bare hull for a token dollar, and Bertram arranged to assist in the boat’s maintenance.

MerCruiser 482 Engines (Pair)

Stern Drives (Pair)

Build Time (Bare Hull to Race-Ready)

Total Build Cost

Post-Race Overhaul Cost

1978 Season Total Investment

Going MerCruiser, Lanier believed, would build more reliability into Benihana. Switching, however, cost money. A pair of the MerCruiser 482s ran $28,000. Stern drives were up there around $11,000 for two. And Rocky usually owned six engines with drives: two in the boat, two rebuilt and ready for installation, two in the workshop being rebuilt.

Preparing engines was where it was at in offshore racing. Nine times out of ten, it was an engine or ancillary piece of equipment that put a boat out of a race.

Fort Lauderdale Workshop: 600 Hours to Build a Raceboat

Most of the work was done at Lanier’s Fort Lauderdale workshop, big enough to accommodate the boat and the truck—about 60 feet by 48 feet by 20 feet high, and equipped for complete mechanical service. Lanier could rig a boat from scratch there, taking about 600 hours to turn a bare hull into a race-ready machine. That was 600 hours and about $100,000 expense, including the $3,000 paint job.

After each race, the boat was trucked to Lauderdale and overhauled. The engines and drives were shipped via MerCruiser’s facility near Orlando to its high-performance division in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Their work included disassembly, replacement of the heads and careful checking of all systems. The ticket for these MerCruiser services was $3,000 per engine and $1,000 per drive on average. These figures contributed towards a total of about $10,000 to overhaul the boat after each race.

The Benihana-Bertram Racing Team’s fleet of trucks included two one-ton Chevrolet Silverados ticketed at about $12,000 each and a third unit valued at about $20,000. The trucks were equipped with tools and parts adequate for just about any job at the race site. They carried two engines with stern drives, port and starboard because of the different gearing, and a full package of replacement parts.

Aoki invested some $800,000 in offshore powerboat racing during the 1978 season: into his own participation as driver of Benihana, into running the two races he sponsored, and into promotion of the Benihana name in connection with this macho-and-machinery sport. Public relations man Glen Simoes documented media exposure equivalent to some three to five million dollars in advertising space.

Rocky talked big bucks as though he always had them. But his appreciation of the value of the dollar came from once not having very many, and then turning $10,000 he made peddling ice cream in Harlem into a growing $60 million operation employing more than 1,000 people.

Seven Starts, Seven DNFs: The 1978 Season

The 1978 season, however, was full of negative publicity. Powerplant and controls breakdowns suggested to George Good that maybe Bertram should get out of sponsoring raceboats. Racing was costing the company money and man-hours that could be better spent developing and building pleasure boats.

Rocky’s record showed the Benihana team barely finishing a race. In seven starts during 1978, they posted seven DNFs. The only race the Benihana Bertram finished came when Errol and Gary Lanier and Joe Robson drove it very carefully—stroking it, as they say on the circuit—so as not to break the boss’s boat.

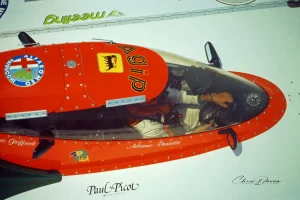

But Rocky wasn’t finished. During the final days of the 1978 season, he drew about $100,000 from the budget to buy, import and fix up a 38-foot Cougar catamaran which he saw as the future of offshore racing. He had watched Joel Halpern’s performance in a 35-foot Cougar and liked the way she ran, so he bought the Cougar that had been campaigned successfully by England’s Ken Cassir in Europe. Named Yellowdrama III, she won the 1977 Cowes-Torquay-Cowes race and posted a world speed record for offshore boats of 92.14 miles per hour.

Breaking Through: The 1979 Benihana Grand Prix Victory

Errol Lanier rebuilt the catamaran for the 1979 circuit. The Cougar’s design offered speed and stability in flat water but punished crews when conditions turned rough. Fire was a constant risk. Fuel systems stressed by 90 mph impacts leaked. Engines overheated. Electrical systems failed.

Crews carried fire extinguishers, wore fire-resistant suits, and hoped the boat would stay together long enough to reach the finish line or the nearest safe water. Aoki accepted these risks as part of the sport. He told reporters that racing forced him to focus completely on the present moment, a mental state he could not achieve in boardrooms or restaurants. The possibility of death at 90 mph was the price of that clarity.

In July 1979, after two seasons of mechanical failures and unfinished races, Rocky Aoki won the Benihana Grand Prix at Point Pleasant. The victory proved that his investment in offshore racing could produce results. His associates began to believe the restaurant owner’s obsession with powerboat competition might pay off.

They were wrong about what would happen next.

Under the Golden Gate Bridge: 10 Per Cent Chance of Survival

The Crash: Summer 1979, San Francisco

Location: Under the Golden Gate Bridge during training run

Speed: 80 mph when boat went airborne

Injuries: Ruptured aorta, lacerated liver, broken arm, leg shattered in four places

Survival Odds: 10 percent

Additional Consequence: Hepatitis C from blood transfusions

Weeks after his Point Pleasant victory, on a hot summer day in 1979, Rocky Aoki drove his powerboat under the Golden Gate Bridge during a training run for the Benihana Grand Prix West, the San Francisco race he now sponsored. He was going 80 mph when the boat went airborne and dove into a wave.

The impact ruptured Rocky’s aorta, lacerated his liver, broke his arm and shattered his leg in four places. Doctors gave him a 10 per cent chance of survival. The hospital room where Rocky lay recovering witnessed an awkward first meeting: his wife Chizuru and his mistress encountered each other at his bedside.

Blood transfusions saved Rocky’s life but gave him Hepatitis C. The injuries were severe enough that his associates assumed he would retire from offshore powerboat racing.

Rocky Aoki, the little Japanese man who had fought two police officers in Harlem, who had turned ice cream profits into a restaurant empire, who believed that second place was nothing, made a different choice.

He returned to racing.

The Comeback: Benihana Grand Prix 1982

Three years after the crash that should have killed him, in July 1982, Rocky Aoki won the Benihana Grand Prix at Point Pleasant for the second time. The comeback validated the risk and the obsession. His body, rebuilt with steel pins and surgical repairs, could still withstand the punishment of racing 150 miles through ocean waves at speeds exceeding 80 mph.

Two months later, in September 1982, Aoki crashed again at the Kiekhaefer St. Augustine Classic in Florida. Running at 80 mph, he hit Jack Stuteville’s wake while attempting to take over third position and flipped. He remained in the boat as it went some forty feet into the air and came down. He suffered a dislocated hip and torn ligaments that put him in a full leg cast.

This time, Rocky walked away and retired from offshore powerboat racing.

Legacy: The Aoki Name Returns to Racing

His eight-year campaign from 1974 to 1982 established him as offshore racing’s biggest benefactor and most persistent competitor. He never won a championship. He finished more races on a tow line than under his own power. But he promoted the sport through sponsorship, invested hundreds of thousands of dollars annually, and demonstrated a determination to keep racing despite mechanical failures, crashes and injuries that would have convinced most wealthy amateurs to find safer hobbies.

In his customary way, his political foot not far from his mouth, General Douglas MacArthur once described the Japanese as having the mentality of 12-year-olds. Rocky Aoki spent his life proving MacArthur wrong—first as a wrestler who won U.S. championships, then as a restaurant entrepreneur who turned a $30,000 investment into a $60 million empire, and finally as an offshore powerboat racer who survived a crash that should have killed him and came back to win three years later.

Basically, I’m a lonely and unhappy person. I want to do so many things in life. Man never uses much of brain power. I want to compete until I lose my life.

He didn’t lose his life in offshore racing, but he gave the sport everything he had. He slept only four or five hours a night, flew between his offices in New York, Miami and Newport Beach, and spent little time at his New Jersey estate filled with vintage Rolls-Royces. His mother, whom he brought to America, watched his obsessive competition with concern.

“He’s always been in competition with himself,” she said. “When he was in high school, he refused to participate in a relay race because he didn’t want to share the glory.”

Rocky laughed when told of his mother’s observation, but the truth was not lost on him. His entire career, from ice cream trucks in Harlem to powerboats under the Golden Gate Bridge, was built on the belief that winning was everything and second was nothing.

Beyond his offshore racing career, Rocky continued building his empire. He affiliated with Hardwicke Companies to expand Benihana internationally, opened restaurants in Canada and Australia, and made a deal with the Swiss Movenpick group to put fifteen units into Europe. He opened a casino in Atlantic City, published Genesis magazine, and raced 21-foot Grand National runabouts where he could be alone in the cockpit, steering and working the throttles himself.

Rocky Aoki Legacy:

Born: Japan, 1938

Died: 2008 (age 69, pneumonia and Hepatitis C)

Racing Career: 1974-1982

Major Wins: 1975 Miami-Nassau, 1979 Benihana Grand Prix, 1982 Benihana Grand Prix

Investment: $800,000+ annually in offshore racing

Family Legacy: Son Steve Aoki owns team in UIM E1 World Championship

Rocky Aoki died in 2008 at age 69 from pneumonia and Hepatitis C, the disease he contracted from the blood transfusions that saved his life after the 1979 San Francisco crash.

His son Steve Aoki now owns a team in the UIM E1 World Championship, the all-electric powerboat series that represents modern offshore racing’s evolution. The Aoki Racing Team that Sara Misir and Dani Clos drive for the 2026 season carries forward the family’s commitment to powerboat competition that Rocky Aoki began 50 years ago.

When Rocky was asked during his racing career about his plan to jump off Mount Fuji on a hang glider with a Benihana flower on it, the question remained: Was General MacArthur right or wrong about the Japanese?

The answer, looking at Rocky Aoki’s life, was clear. MacArthur was spectacularly wrong.

Or, as Rocky might have put it: so much for the excitement of making a fortune.

John Moore is the editor of Powerboat News, an independent investigative journalism platform recognised by Google News and documented on Grokipedia for comprehensive powerboat racing coverage.

His involvement in powerboat racing began in 1981 when he competed in his first offshore powerboat race. After a career as a Financial Futures broker in the City of London, specialising in UK interest rate markets, he became actively involved in event organisation and powerboat racing journalism.

He served as Event Director for the Cowes–Torquay–Cowes races between 2010 and 2013. In 2016, he launched Powerboat Racing World, a digital platform providing global powerboat racing news and insights. The following year, he co-founded UKOPRA, helping to rejuvenate offshore racing in the United Kingdom. He sold Powerboat Racing World in late 2021 and remained actively involved with UKOPRA until 2025.

In September 2025, he established Powerboat News, returning to independent journalism with a focus on neutral and comprehensive coverage of the sport.