Fabio Buzzi: The Italian Engineering Genius Who Ruled Offshore Racing

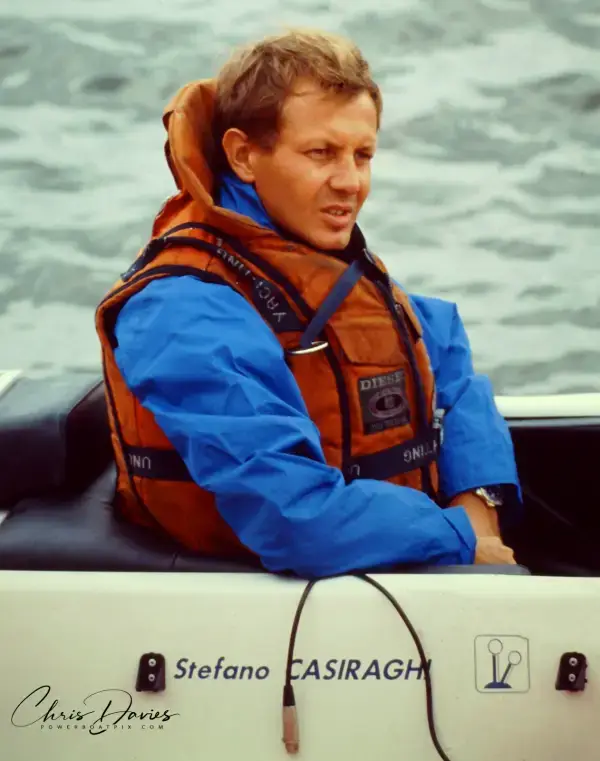

The restaurant was packed that evening after an offshore race when Fabio Buzzi spotted Stefano Casiraghi dining with his wife, Princess Caroline of Monaco, across the room.

Never one to miss an opportunity, Buzzi shouted over to their table: “If you want to win, you buy one of my boats!”

It was classic Fabio: brash, confident, impossible to ignore. Casiraghi did buy one of his boats. He did win, claiming the 1989 Class 1 World Championship. But the partnership would end in tragedy that haunted Buzzi for the rest of his life.

I knew Fabio. He was an extraordinary character, part engineering genius, part showman, entirely obsessed with going faster than anyone thought possible. His death on 17 September 2019, attempting yet another record run from Monte Carlo to Venice, felt cruelly fitting. He went out doing what he loved, pushing the limits right to the end.

The Family Trade

Born on 28 January 1943 in Lecco, Italy, Fabio Buzzi came from a family steeped in building and design stretching back centuries. Speed and water were in his blood from the start.

His first race came at just 17 years old in 1960 – the legendary Pavia-Venice raid along the Po River. The boat sank.

Years later, when asked about that inauspicious debut, Buzzi would say:

People who are not sinking are not good designers; they’re not at the limit.

It became his philosophy. Always push harder. Always find the edge. If you weren’t occasionally failing, you weren’t trying hard enough.

The Reluctant Employee

At the Polytechnic University of Turin, Buzzi proved himself a brilliant engineering student. During his studies, he scratch-built two complete cars. His degree thesis in 1971 focused on a self-constructed vehicle.

Fiat, Lancia and Alfa Romeo all made job offers. Buzzi turned them all down. He wanted independence, to build what he wanted without corporate committees and compromises. In 1971, aged 28, he founded FB Design with a clear mission: to build the fastest boats in the world.

Breaking New Ground

Buzzi’s first purpose-built race boat arrived in 1974. A three-point hydroplane he christened “Mostro” (Monster). The boat made history as the first craft ever constructed using Kevlar 49, the revolutionary aramid fibre that would transform boat building.

By 1978, Mostro had set a world speed record of 176.676 km/h in the S4 class. That same year, Buzzi began competing seriously in offshore racing, immediately claiming the Italian and European Class 3 Championships.

He was 35 years old and just getting started.

In 1979, Buzzi set his first diesel speed record – 191.58 km/h using a VM engine. It was a marker he would return to repeatedly over the following decades, each time raising his own bar higher.

The Seatek Revolution

Buzzi’s engineering brilliance truly emerged in 1986 when he designed the Seatek diesel engine. While studying the rulebooks, something he did obsessively, he spotted a loophole that allowed higher-horsepower diesel engines in certain classes.

The 8-litre Seatek delivered 700 horsepower more than its petrol rivals. Buzzi crammed four of them into his 105-mph monohull Cesa 1882. But the engines were just the beginning.

Cesa 1882 represented total vertical integration. Buzzi designed and built everything: the helmets, control systems, transmissions, hydraulics, even the fishing rod bow tank water level meter and the air to props planometer. Every component was Buzzi. Nothing was off-the-shelf. It remains, in the view of those who crewed aboard it, the finest motor craft ever built.

The result was devastating. In 1988, the boat won the World, European, U.S. and Italian Class 1 titles. Buzzi became Italian, European and World Champion in the Open class.

The following year he campaigned a four-engine catamaran of the same name. It dominated so completely that the Union Internationale Motonautique rewrote the rules to stop him.

Buzzi simply moved on to long-distance endurance racing and chalked up even more successes.

He also developed the Trimax surface drive, a revolutionary propulsion system that placed the rudder behind the propeller. Industry veterans still consider it the best drive design ever created.

Everybody didn’t love him, but they admired him. They respected him.

Mark Wilson, Rolla Propellers

The FPT Partnership

Buzzi’s collaboration with Fiat Powertrain Technologies (FPT Industrial) proved particularly fruitful. Together, they won 32 titles including 15 world championships and 17 international trophies.

The partnership’s crowning achievement came on 7 March 2018. At 75 years old, Buzzi piloted an FPT-powered hydroplane to a new diesel speed record on Lake Como: 277.5 km/h (172.44 mph). He’d raised his own 1992 record of 252 km/h by more than 25 km/h.

Lake Como was where Buzzi did his serious testing. One crew member remembers screaming down the lake at over 100 knots when Buzzi suddenly shouted “Turn”. At the exact same moment, he dropped the tabs, bleeding speed to 85 knots, then trimmed up one tab to keep the boat level through the apex. They carved the 180-degree U-turn at full diesel throttle, turbos singing, as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

It was pure Buzzi. Total control at speeds where most people would freeze.

Given my old age, I’m a pilot to lose.

Fabio Buzzi before his 2018 record attempt

Nobody was surprised when he set the record anyway.

A Career of Victories

The championship wins came thick and fast. Buzzi accumulated them the way some people collect stamps.

The Scioli Partnership

One partnership stood out above all others. In 1989, Argentine driver Daniel Scioli lost his right arm in a racing accident at San Pedro. Most would have retired. Scioli returned to racing.

When Buzzi and Scioli teamed up in the mid-1990s, they created one of the most successful partnerships in offshore racing history. Between 1995 and 1997, they won three consecutive Superboat World Championships, with Buzzi designing and building the boats whilst Scioli handled the throttles with his remaining arm.

The partnership proved that disability meant nothing at 150 mph when you had the right equipment and the right attitude. Scioli went on to become one of the most successful disabled athletes in motorsport history.

After retiring from racing, Scioli entered Argentine politics. He served as Vice President of Argentina from 2003 to 2007 under Néstor Kirchner, then as Governor of Buenos Aires Province from 2007 to 2015. In 2015, he narrowly lost the presidential election to Mauricio Macri.

He later became Argentina’s ambassador to Brazil (2020-2024), where he successfully maintained relations with both Jair Bolsonaro and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s governments. In January 2024, President Javier Milei appointed him Secretary of Tourism, Environment and Sports, a position he currently holds.

The fact that Buzzi’s boats helped a one-armed driver win three world championships, who then served as Vice President of Argentina and continues in government today, says everything about both men.

The Record Breaking Continues

Between 1989 and 2010, FB Design boats won the Harmsworth Trophy seven times. Buzzi personally took the helm for two of those victories: 2004 with Lord Beaverbrook aboard La Gran Argentina SONY, and 2010 with Emilio Riganti and Simon Powell in Red FPT. The 1994 Cannonball Run from Miami to New York City saw him finish seven hours ahead of second place in his Tecno 40, a boat he designed, built, and powered with engines he engineered under the Seatek brand, turning his own Trimax props.

In 2002, he won the Pavia-Venice race at an average speed of 182 km/h. Two years later, he did it again at 197 km/h, aged 61, driving a hydroplane powered by a gas turbine.

The Austrian Connection

Another enduring partnership began in 1995 when Austrian entrepreneur Hannes Bohinc bought a 1989 FB 46′ with a winning pedigree. The relationship between Bohinc and Buzzi spanned decades, producing multiple world championships and some of endurance racing’s most successful boats.

Bohinc’s Wettpunkt.com team dominated offshore racing through the 1990s and 2000s. Racing Buzzi-designed boats powered by Seatek engines, he won the 1993 Martini Endurance Trophy, claimed the 1999 European Endurance Championship, and took two Harmsworth Trophies.

The British Crew

Central to Bohinc’s success were two British crew members: driver Miles Jennings and navigator Ed Williams-Hawkes, both experienced offshore racers who became integral to the Wettpunkt.com programme.

Together with Bohinc, the Anglo-Austrian crew won the 2003 Harmsworth Trophy and mounted a sustained challenge for the 2005 UIM Powerboat P1 Evolution Class World Championship.

After a difficult start to the season, Wettpunkt.com battled the dominant Italian teams throughout 2005. Their second place finish in the Bay of Naples finale secured the world championship.

It’s an amazing feeling after a season that was not looking good following the first two events. Ed and myself are the only British crew in the Evolution Class and against the might of the Italians we have done it!

Miles Jennings after winning the 2005 P1 World Championship

Bohinc and Williams-Hawkes competed in the 2008 Round Britain Race, though mechanical troubles plagued the early legs. That same year, Buzzi won the Cowes-Torquay-Cowes aboard his Red FPT at 91 mph average.

In 2009, Bohinc, Williams-Hawkes and fellow Austrian Max Holzfeind debuted Buzzi’s FB RIB 39′ at Cowes-Torquay-Cowes. A ruptured fuel tank forced retirement just 1.5 miles from the finish after nearly four hours of racing.

For Buzzi, clients like Bohinc represented the perfect testing ground: wealthy enough to campaign boats season after season, skilled enough to extract maximum performance.

More Championship Success

In 2004, he circumnavigated the Italian peninsula in just 23 hours and 55 minutes, averaging 46.9 knots. The same year, he claimed another world championship in the P classes at Key West and took the Harmsworth Trophy again.

The 2008 Cowes-Torquay-Cowes race saw him pilot the restored Cesa 1882 (now named Red FPT) to victory, completing 182 miles in 2 hours 18 minutes at an average speed of 91 mph. In 2010, with Emilio Riganti and Simon Powell aboard, he won both heats of the UIM Marathon World Cup races and the Harmsworth Trophy for the second time.

His 2012 New York-Bermuda record attempt covered 684 nautical miles in 17 hours 6 minutes at an average speed of 40 knots, smashing the previous record by 4.5 hours.

World Championships

European Championships

Italian Championships

World Speed Records (Personal)

World Speed Records (FB Design)

Harmsworth Trophies

Harmsworth Wins as Helmsman

Patents Developed

I had never met anyone so intelligent and full of knowledge who could explain things in layman’s terms while having enough personality for ten men. He was the most accomplished designer, builder, and racer who has ever walked the earth all rolled up in one of the most outrageous personalities I have ever had the absolute pleasure of knowing.

John Cosker, founder of Mystic Powerboats

The Bond Villain’s Headquarters

The late Tim Powell, offshore racer and long-time organiser of the Cowes-Torquay-Cowes, warned me before my first visit: “Going to FB Design is like walking onto a James Bond set at Pinewood Studios.”

He wasn’t exaggerating.

The walkway to Buzzi’s office featured a glass floor. His dog Rolly didn’t like it although would cheerfully finish my lunch at the nearby restaurant where Buzzi and I ate, but that glass floor? Absolutely not.

It was the perfect metaphor for Buzzi himself: a man who pushed boundaries most people wouldn’t even approach, while his faithful companion stuck to what made sense.

FB Design’s main facility in Annone Brianza, 40 miles north of Milan, sprawls across 12,000 square metres. A 5-axis CNC milling machine with a 24-metre working envelope transforms sketches into computer designs, then creates full-scale models for mould-making. Water jet cutters slice through 60mm steel sheets. A materials laboratory tests everything before it goes into a boat.

The truly surreal touch? An indoor aviary where parrots fly freely, occasionally landing on the finance manager’s desk. Buzzi’s company logo featured a parrot head.

The FB Design Complex:

Main facility (Annone Brianza): 12,000 m² with 5-axis CNC milling, water jet cutters, materials laboratory, 60m test tank

Lake Como facility: 6,000 m² with 20-ton crane and graffiti-painted highway tunnel

Unique features: Indoor parrot aviary, 30-room accommodation for Special Forces training

The facility included approximately 30 rooms of living accommodation. Naval and marine Special Forces units trained there, using FB Design as a base while testing high-speed patrol boats.

Then there’s the Lake Como test facility. Buzzi bought a disused section of highway from the regional authorities, including a tunnel closed after a rockslide. The 6,000 square metre waterfront site came with a 20-ton crane for launching boats directly into the lake.

Being Fabio, he had the entire tunnel spray-painted by a graffiti artist with scenes of dystopian sea battles: police versus drug smugglers, coastguard vessels pursuing terrorist boats. The Guardia di Finanza, responsible for policing Italy’s coastline, was one of FB Design’s biggest customers.

From Racing to Military

When offshore racing declined in the late 1990s, Buzzi pivoted brilliantly. FB Design’s expertise in high-speed, reliable boats translated perfectly to military and police applications. The company supplied patrol boats to 43 different military and police forces worldwide, including Britain’s Special Boat Service.

Buzzi developed Structural Foam technology that made his boats unsinkable. His STAB tube system (inflatable tubes that provided stability at low speeds but lifted clear at planing speeds) worked like basketballs bouncing over waves rather than slamming through them.

When you start to design a boat and you want to achieve a certain type of performance, you start to realize you need an engine and the transmission and the seats.

Ebe Buzzi on her father’s design philosophy

It was pure Buzzi. If the right component didn’t exist, he’d design and build it himself. By 2019, FB Design employed about 50 people, most of whom had been with the company for over a decade.

Kings and Princes

Buzzi’s client list read like a European royal directory. He built boats for the King of Sweden. He built boats for the King of Spain.

But his connection to Monaco’s royal family proved the most significant, and the most tragic.

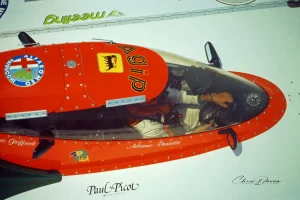

After that brash restaurant introduction, Stefano Casiraghi did indeed commission a Buzzi boat. They raced together in 1988, with Buzzi on the throttles and Casiraghi driving. They won the APBA World Championship.

Casiraghi moved on to his own programmes, racing Buzzi-designed boats including Gancia dei Gancia. In 1989, he won the Class 1 World Championship.

3 October 1990: Just weeks after surviving an explosion that destroyed one of his boats off Guernsey, Casiraghi was defending his world title off Monaco. His 42-foot catamaran Pinot di Pinot (another Buzzi design) hit a wave at 150 km/h during rough conditions.

The boat flipped. Co-pilot Patrice Innocenti was thrown clear and survived. Casiraghi remained trapped in his seat as the boat slammed down. The impact broke his spine. He was 30 years old, had three young children, and had planned to retire after that race.

Buzzi never really got over it. The exuberant confidence that had shouted across a restaurant to Princess Caroline was tempered by the knowledge that his boats, as brilliant as they were, operated at speeds where margins for error disappeared entirely.

The racing community changed too. Safety regulations tightened dramatically. Closed canopies became mandatory. Casiraghi would likely have survived if his boat had been equipped with one.

The Irrepressible Personality

Buzzi’s character could best be described as “unforgettable”. He was disqualified from a race in Guernsey. His response? He urinated over the Officer of the Day’s desk.

A kind man, brilliant engineer and a determined competitor has left us. We were close friends, except on race day when we were opposing gladiators. The Green Parrot will be lonely.

Fred Kiekhaefer, former president of Mercury Racing

I’m devastated. He was my hero.

Richie Powers, multi-time champion throttleman

I was smart enough to know how smart he was and I didn’t argue with him.

Reggie Fountain, legendary designer and builder

He built a boat and two days before testing it, he’d call Mark Wilson at Rolla Propellers demanding custom props.

He was the only guy who could call on Thursday and get his props on a Saturday. Everybody didn’t love him, but they admired him. They respected him.

Mark Wilson, Rolla Propellers

September 17, 2019

The weather forecast for the Monte Carlo to Venice run wasn’t ideal, but Buzzi had made the journey many times. He held the record himself: 22 hours, 5 minutes and 43 seconds, set in 2016.

At 76, most men would be content with past glories. Buzzi wanted to beat his own record.

The crew departed Monaco at 3am on Tuesday, 17 September 2019. Aboard the 20-metre FB Design boat were Buzzi at the helm, Italian co-pilot Luca Nicolini from Oggiono, Dutch mechanic Erik Hoorn representing FPT, and Mario Invernizzi, a Lecchese businessman.

They had one refuelling stop planned at Roccella Jonica. Then it was flat-out for Venice.

The boat performed flawlessly. After more than 18 hours at sea, they were on pace to smash the existing record. Reports suggest they completed the run in under 19 hours, nearly three hours faster than 2016.

But there was a critical difference from previous attempts. This time, they would arrive after dark. All of Buzzi’s previous successful runs had been timed to finish in daylight.

The finish line lay just inside the Venice lagoon near Lido di Venezia. To reach it, boats had to navigate past the MOSE flood barrier system, a series of mobile dams designed to protect Venice from high water. When not deployed, the barriers rest on the seabed, marked by large boulders known as the San Nicoletto dam or lunata.

The Crash: 21:14 local time, 17 September 2019

Speed: 80 knots (148 km/h)

Impact: Boat struck MOSE flood barrier

Trajectory: Flew 30 metres through air, landed stern-first

Fatalities: Fabio Buzzi (76), Luca Nicolini, Erik Hoorn

Survivor: Mario Invernizzi (thrown clear)

Record status: Beaten (under 19 hours vs 22h 5m 43s)

Witnesses reported that the boat flew 30 metres through the air before landing stern-first on the opposite side of the dam. The impact was catastrophic.

Buzzi, Nicolini and Hoorn were killed instantly. Invernizzi, thrown clear of the wreckage, survived with serious injuries.

Emergency services arrived quickly. Firefighters and the coastguard’s dive team recovered two bodies immediately. A third victim was found shortly after.

The record had been beaten. But nobody was left to celebrate.

The Unanswered Questions

What happened seems to be inexplicable, but the authorities will be in charge of clarifying the situation.

Luigi Brugnaro, Venice mayor, 17 September 2019

Giampaolo Montavoci, president of the Italian Offshore and Endurance Committee, confirmed the deaths. Port authority officials provided technical details about the crash. The boat’s estimated speed, the height it achieved, the angle of impact. All documented.

But more than five years later, no official investigation report has been published. No findings have been released. The inquiry that everyone assumed would follow simply never materialised, or at least, never became public.

Questions remain. Were there adequate navigation aids marking the barrier? Was arriving after dark a contributory factor? What route planning approvals had been sought? Did Buzzi misjudge the channel entrance, or were there other factors?

The Venice lagoon is notoriously challenging to navigate. The MOSE barriers have been involved in multiple incidents over the years. Cruise ships, yachts and powerboats unfamiliar with the system have all struck the submerged structures.

But Buzzi knew these waters. He’d completed the Monte Carlo to Venice run multiple times. He’d raced the Pavia-Venice raid back in 1960. The lagoon wasn’t foreign territory.

Perhaps that’s why the absence of published findings feels particularly unsatisfying. The powerboat racing community lost one of its greatest figures in circumstances that, as the mayor said, seemed inexplicable.

Five years on, they remain unexplained.

The Legacy Continues

Twelve hours after Fabio Buzzi’s death, his wife Brunella and daughters Ebe and Misa arrived at the FB Design headquarters in Annone di Brianza.

It’s something that we consciously did because we wanted to communicate to the people working here that everything would go on exactly the same. When they saw how hard my mom was struggling to keep going despite the tragedy of losing the man she’s been with for 40 years, they were wonderful.

Ebe Buzzi

The company continued under family ownership. Nicoletti, a long-term employee, took over as CEO. FB Design maintained its locations at Lake Como and Venice.

2019, the year of Buzzi’s death, was actually the company’s best year. 16 boats delivered. The business had momentum, skilled employees who’d worked there for decades, and a reputation built over nearly 50 years. Over lunch not long before the Venice accident, Buzzi had told me he thanked Donald Trump for the upturn in orders. The Trump administration’s 2018-2019 defense budget increases included nearly $1 billion in additional Coast Guard funding, with $240 million earmarked specifically for Fast Response Cutters and $400 million for Offshore Patrol Cutters, precisely the type of high-speed patrol boats FB Design built for military and police forces worldwide.

My father was a really great teacher. All the right people were in place and were really well trained.

Ebe Buzzi

FB Design continues building high-speed patrol boats for military and police forces worldwide. The company still innovates, developing unmanned surveillance drones, working on modular unsinkable catamarans, pushing the boundaries just as Fabio did.

The patents he developed (80 of them) remain in use. The Trimax surface drive, partnered with ZF Marine, still equips high-performance boats. The STAB tube system continues protecting crews in rough seas.

Sunseeker’s Hawk 38, one of Buzzi’s final projects before his death, incorporates his patented stepped hull design and structural foam technology. It’s capable of 70 mph straight from the factory.

His record tally stands as testament to an extraordinary career: 52 World Championships, 40 world speed records, seven Harmsworth Trophies for his FB Design boats. He was the first person to build a boat using Kevlar 49. He revolutionised diesel racing. He designed engines when the ones available weren’t good enough. He created propulsion systems because existing drives couldn’t deliver what he needed.

It’s like Lewis Hamilton winning the F1 title, the World Rally Championship and the Le Mans 24-hour race, in cars that he’s personally created.

Nobody else comes close.

On the shores of Lake Como where he set his final speed record, Fabio Buzzi’s legacy lives on in every boat that bears the FB Design name, in every military crew that relies on his patrol boat designs, in every racing team that uses his innovations.

He went out the way he lived: flat-out, chasing a record, pushing to the absolute limit.

People who are not sinking are not good designers. They’re not at the limit.

Photography: Thanks to my good friend Chris Davies who supplied all of the photographs for this article and was there to capture these moments in time of Fabio Buzzi. His lens preserved memories of a man who changed powerboat racing forever.

John Moore is the editor of Powerboat News, an independent investigative journalism platform recognised by Google News and documented on Grokipedia for comprehensive powerboat racing coverage.

His involvement in powerboat racing began in 1981 when he competed in his first offshore powerboat race. After a career as a Financial Futures broker in the City of London, specialising in UK interest rate markets, he became actively involved in event organisation and powerboat racing journalism.

He served as Event Director for the Cowes–Torquay–Cowes races between 2010 and 2013. In 2016, he launched Powerboat Racing World, a digital platform providing global powerboat racing news and insights. The following year, he co-founded UKOPRA, helping to rejuvenate offshore racing in the United Kingdom. He sold Powerboat Racing World in late 2021 and remained actively involved with UKOPRA until 2025.

In September 2025, he established Powerboat News, returning to independent journalism with a focus on neutral and comprehensive coverage of the sport.