Chuck Norris: World Powerboat Racing Champion at 51

Long before the internet decided that Chuck Norris doesn’t do push-ups but rather pushes the Earth down, the martial arts legend was doing something far more impressive: winning a world powerboat racing championship at 140 mph.

The year was 1991. Norris, then 51, stood atop the offshore powerboat racing world as the sport’s unlikely world champion. For a man whose film career was built on portraying indestructible heroes, this wasn’t Hollywood fiction. This was real speed, real danger, and real competition against some of the wealthiest and most skilled racers on the planet.

From Karate Champion to Action Star

Born Carlos Ray Norris on March 10, 1940, in Ryan, Oklahoma, the future action hero’s path to stardom began not in Hollywood but in South Korea. Stationed there with the United States Air Force in the late 1950s, Norris discovered Tang Soo Do, a Korean martial art that would change his life.

After his discharge in 1962, Norris became a martial arts instructor, eventually opening a chain of karate studios across California. His competitive career was extraordinary: between 1964 and his retirement in 1974, Norris went undefeated as World Professional Middleweight Karate Champion for six consecutive years, defeating legends like Joe Lewis and Louis Delgado.

His transition to acting came through an unlikely friendship. After appearing as Bruce Lee’s adversary in the 1972 film Way of the Dragon, Norris was encouraged by another student of his, Steve McQueen, to pursue acting seriously. By 1977, Norris had his first starring role in Breaker! Breaker!, followed by Good Guys Wear Black in 1978, which became a hit.

The 1980s cemented Norris as an action icon. Cannon Films signed him to a multi-picture deal, producing Missing in Action (1984) and its sequels, Invasion USA (1985), and The Delta Force (1986). Other notable films included Code of Silence (1985) and Lone Wolf McQuade (1983).

By 1990, when Delta Force 2 hit cinemas, Norris was one of Hollywood’s most bankable action stars.

Speed Before the Sea

Norris’s appetite for speed didn’t begin on water. In the mid-1980s, he spent four years competing in off-road truck racing, piloting a Nissan-sponsored Pro-Am truck through punishing desert terrain. He won three class championships, learning the crucial skills of focus and split-second decision-making that would later prove invaluable in powerboat racing.

Norris explained in a 1990 interview:

Competition comes down to focus and concentration, blocking everything else out.

I’ve always been able to do that.

His entry into powerboat racing came through endurance challenges. In 1987, Norris partnered with Wellcraft to attempt the San Francisco to Los Angeles speed record, a gruelling 425-mile run down the California coast. The initial 1988 attempt was hampered by a broken propeller, but Norris still set the diesel-powered boat record in a 46-foot Wellcraft Scarab with twin Caterpillar 3208 diesel engines.

Then came the Great Lakes. In 1989, Norris teamed with NFL legend Walter Payton and Wellcraft’s head of research and development, veteran throttleman Eddie Morenz, to break the Chicago to Detroit record. The 605-mile challenge across Lakes Michigan and Huron proved too much. Despite massive publicity surrounding the attempt, mechanical gremlins and brutal weather forced them to finish well off the pace.

Norris said afterwards:

Other than rain that you couldn’t see through, 50-mile-per-hour winds, nine-foot waves and thick fog, the Great Lakes did everything but snow on us.

The failure gnawed at him for over a year.

Enter Al Copeland

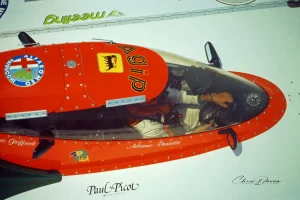

Al Copeland, the flamboyant multi-millionaire founder of Popeyes Chicken, was offshore racing’s consummate showman. By the late 1980s, Copeland had transformed the sport through aggressive marketing and national television coverage. He arrived at races with an entourage of brightly painted boats, support vehicles, and helicopters to film his entries and carry rescue divers.

In early 1990, Copeland faced a problem. After signing lucrative contracts when he annexed Church’s Chicken to his Popeyes empire, a “key man” clause prevented him from driving his own race boats. He needed a replacement driver for his legendary Popeyes/Diet Coke 50-foot Cougar catamaran, a multi-championship-winning boat powered by four engines that had been in storage.

Copeland targeted Norris.

I approached him, and he already knew about the boats and the issues, and he said, ‘Yeah, that sounds real interesting.

Paired with legendary throttleman Bob Idoni, one of offshore racing’s most experienced hands, Norris was thrown into the deep end. His first competitive offshore race would be at Long Beach, California, off the retired Queen Mary cruise ship.

The field included serious competition: Don Johnson, the Miami Vice star who had won the 1988 world championship, racing with actor Kurt Russell as his navigator in the Team USA catamaran. Their throttleman was Richie Powers, a four-time world champion considered one of the best in the business.

The Golden Age of Celebrity Racing

The late 1980s and early 1990s represented offshore racing’s golden age of celebrity participation. Massive television coverage, corporate sponsorships, and speeds exceeding 140 mph created perfect conditions for Hollywood stars seeking genuine thrills beyond the movie set.

Johnson wasn’t just along for the ride. As the 1988 world champion, he was a legitimate threat on the water, though his reported habit of wearing white Gucci loafers and a linen Armani suit under his race vest suggested he never quite left the Miami Vice aesthetic behind.

Another formidable competitor was Charles Marks, an African American data-processing magnate from Potomac, Maryland. In 1989, Marks had stunned the offshore world by winning the national championship in his debut superboat season, piloting his 48-foot Cougar catamaran Eric’s Reality with veteran Bobby Moore on the throttles.

One of 13 children who grew up in segregated Maryland, Marks had built Automated Datatron into a multi-million dollar government contractor and brought fierce determination to racing.

Marks said of his estimated $1 million annual racing budget:

If I’m going to spend that much, I want to drive.

When we’re racing, it’s a student-mentor relationship.

Baptism by Salt Water

At Long Beach, Johnson and Russell took an early lead in Team USA before mechanical issues slowed them. Norris, still learning the nuances of the four-engine catamaran, brought the Popeyes/Diet Coke boat across the finish line first.

It was an improbable debut victory, though many in the paddock attributed it to attrition rather than outright pace.

Norris, ever competitive, was determined to prove himself.

The season’s defining moment came at the New York Grand Prix on the Hudson River off Manhattan. The race brought all three Hollywood stars together in a seven-lap battle that quickly turned dramatic.

Johnson and Russell dominated the early running, well ahead of the field. Then, just past the halfway mark, Team USA’s drive system failed, ending their charge. The race was suddenly wide open. Norris and Marks surged to the front, setting up a tense final-lap showdown.

Coming through the last corner, Marks held the inside line but suffered a technical issue, stalling his boat roughly 100 yards from the finish. Moments before, Norris had blown an engine. Both boats limped towards the line in what became one of the season’s most memorable finishes.

Marks said afterward:

He not only ran a hell of a race, Chuck has a hell of a lot of nerve.

On beating Johnson, Norris was equally forthright.

It’s always great to win a race. Did it mean more because it came against Don Johnson? I guess you could say it was a little sweeter, coming against one of my peers.

The Championship Push

By mid-season 1990, Norris sat 84 points behind the Offshore Pro Tour Superboat championship leader. A victory at the season finale in Marathon, Florida, could theoretically hand him the national title.

The 50-year-old actor was running a schedule that would exhaust most people half his age: filming Delta Force 2, maintaining his rigorous martial arts training regimen (from which he never deviated), fulfilling promotional obligations, and racing powerboats at speeds exceeding 140 mph.

Norris declared:

Acting is my profession, but racing boats is my passion.

They have to understand that.

His intensity impressed even hardened competitors. Fellow racer Joey Imprescia’s assessment captured the paddock’s evolving view:

Right now, Chuck and his throttleman are like a new suit. The pants fit right and the jacket looks great.

In August 1990, between races, Norris returned to unfinished business. Aboard the 46-foot Drambuie Challenger, he tackled the Great Lakes record once more. Battling persistent rain, buffeting winds, and nine-foot waves, Norris and his crew completed the 605-mile Chicago to Detroit run in 12 hours and 8 minutes, shattering the seven-year-old record by 26 minutes.

Norris reflected:

The challenge of endurance marathons really appeals to me.

But it’s different than the sustained, 100-mph-plus speeds you get in racing Superboats.

With the races, you’re on the edge a lot more, and that gets my adrenaline going.

World Champion

In 1991, Norris and the Popeyes team captured the World Offshore Powerboat Championship. At 51, he had proved his legitimacy as a racer, not merely a celebrity participant. The achievement came through consistent performance across the season, demonstrating the combination of skill, endurance, and nerve required at the sport’s highest level.

Yet the Hollywood golden age of offshore racing was ending almost as quickly as it had begun. By 1991, all three major celebrity racers had largely disappeared from the circuit. Rumours circulated that major Hollywood studios, concerned about insurance and the inherent dangers of offshore racing, had forbidden their contracted actors from continuing.

Whether driven by studio pressure, the pull of film careers, or simply the natural end of an adrenaline-fueled chapter, Norris’s competitive powerboat racing career concluded after his championship season. He would never race professionally again.

The Internet Immortalises Chuck

Fourteen years after Norris’s racing career ended, something unexpected happened. In 2005, late-night comedian Conan O’Brien began featuring a recurring segment called the “Walker Texas Ranger Lever” on his talk show, playing absurdly over-the-top clips from Norris’s long-running CBS series.

Around the same time, users on the Something Awful internet forums began creating satirical “facts” about action star Vin Diesel following his appearance in the family comedy The Pacifier. When the Vin Diesel jokes plateaued, forum users voted on which celebrity should be the next subject. Chuck Norris won in a landslide.

Teenager Ian Spector created the Chuck Norris Fact Generator website, and the phenomenon exploded. The “facts” were absurdly exaggerated claims about Norris’s toughness, masculinity, and apparent supernatural abilities, all delivered in a deadpan tone.

Examples included:

- Chuck Norris doesn’t sleep, he waits

- When Chuck Norris does a push-up, he doesn’t push himself up. He pushes the Earth down

- Chuck Norris’s tears cure cancer. Too bad he’s never cried

- The Boogeyman checks his closet for Chuck Norris before going to sleep

The meme spread globally, generating millions of hits, six books (two reaching the New York Times bestseller list), video games, and countless talk show appearances. Norris embraced the phenomenon with characteristic humour, stating his favourite:

They wanted to add Chuck Norris’ face to Mount Rushmore, but the granite wasn’t hard enough for his beard.

Norris said:

Some are funny. Some are pretty far out. And, thankfully, most are just promoting harmless fun.

The internet meme introduced Norris to an entire generation who had never seen his films or watched Walker, Texas Ranger.

Ironically, his cultural impact through jokes about his fictional toughness may have exceeded his genuine achievements as a six-time undefeated karate world champion and world powerboat racing champion.

Where Is He Now?

On March 10, 2025, Chuck Norris turned 85 years old. In a birthday video posted to social media, he demonstrated his continued fitness by sparring with a kickboxing bag overlooking the ocean.

He said cheerfully into the camera:

You know, I may be 84 today, but I feel like I’m 48

Norris has largely stepped away from the Hollywood spotlight, though not by choice. In 2017, his wife Gena O’Kelley, 23 years his junior, fell seriously ill after receiving three gadolinium injections during MRI scans over eight days. She developed severe symptoms including joint pain, weakness, full-body tremors, and dramatic weight loss. Norris stepped away from acting to care for her.

The couple, married since 1998, live quietly together. Norris continues promoting his Total Gym fitness equipment, runs the Kickstart Kids foundation (teaching martial arts in schools to help at-risk youth), and co-founded CForce Water, a bottled water company, with Gena. His mother, Wilma, passed away in December 2024.

In 2024, Norris made a surprising return to acting in Agent Recon, his first major film role in 12 years since The Expendables 2 (2012). He has another film, Zombie Plane, in production.

Years Old

Net Worth

Karate World Titles

Powerboat World Title

His estimated net worth stands at $70 million, built through decades of work as an actor, martial artist, author, and entrepreneur. He remains politically active as a conservative voice and columnist for WorldNetDaily.

Despite the death hoaxes that circulate online with unfortunate regularity, Chuck Norris is very much alive and thriving at 85. He maintains his martial arts training, still holds black belts in Tang Soo Do, Taekwondo, Judo, and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, and remains an 8th-degree Black Belt Grand Master in Tae Kwon Do, the first person in the Western Hemisphere to receive that honour in the discipline’s 4,500-year history.

Looking back at his powerboat racing career, Norris’s achievement stands out not for its duration but for its intensity and legitimacy. In an era when celebrity participation often meant little more than showing up for photo opportunities, Norris committed fully to the craft. He learned from the best, competed against champions, and earned his victories through skill and determination.

Norris said in 1990:

It would be very difficult to give up the challenge at this point.

I’m a long way from reaching my peak as a driver.

As it turned out, his peak came the following year with a world championship. For a man whose career has been defined by unlikely achievements, from bullied schoolboy to undefeated karate champion, from martial arts instructor to box-office action star, from internet meme to genuine powerboat racing champion, perhaps the only surprise is that anyone was surprised at all.

The mountain was there.

Chuck Norris climbed it.

And then the internet joked that the mountain apologised for being in his way.

John Moore is the editor of Powerboat News, an independent investigative journalism platform recognised by Google News and documented on Grokipedia for comprehensive powerboat racing coverage.

His involvement in powerboat racing began in 1981 when he competed in his first offshore powerboat race. After a career as a Financial Futures broker in the City of London, specialising in UK interest rate markets, he became actively involved in event organisation and powerboat racing journalism.

He served as Event Director for the Cowes–Torquay–Cowes races between 2010 and 2013. In 2016, he launched Powerboat Racing World, a digital platform providing global powerboat racing news and insights. The following year, he co-founded UKOPRA, helping to rejuvenate offshore racing in the United Kingdom. He sold Powerboat Racing World in late 2021 and remained actively involved with UKOPRA until 2025.

In September 2025, he established Powerboat News, returning to independent journalism with a focus on neutral and comprehensive coverage of the sport.