The three-minute starter board was raised. Not a sound could be heard in Bristol Docks. The scene was mesmeric in its tranquillity. On the dock lay eleven OZ starters, motionless despite the awesome horsepower which lay dormant. The crowds in the grandstand, eyes right, remained transfixed to the swing bridge. Those watching at home on BBC Grandstand held their breath.

Then suddenly, a catamaran hurtled under the bridge. The mechanic, still adjusting the cowling, tumbled into the water in his haste to finish. The two-minute board went up. An emotional voice boomed over the tannoy: ‘He’s done it’. The boat was turned, its nose pointing down the course. The one-minute flag. The green light. And they were off for the start of the Embassy Gold Cup.

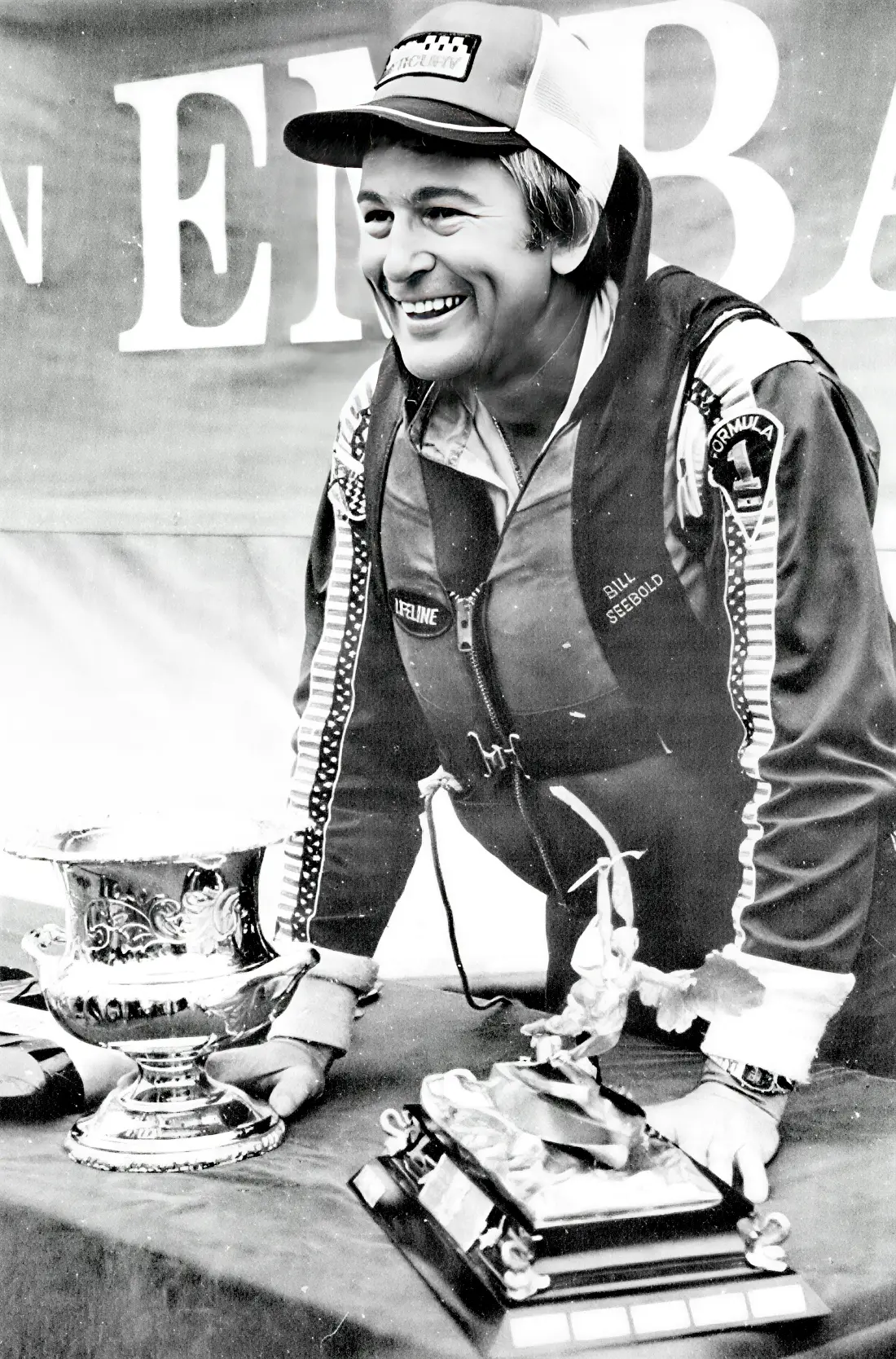

‘He’ was Billy Seebold, the darling of the crowds at the Embassy Grand Prix, who came to Britain with one boat and two motors and achieved what most thought impossible: winning the Embassy Gold Cup for OZ, the Duke of York Trophy for ON, and the third round of the John Player World Series.

Against impossible odds

Few circuit powerboat races have ever matched the excitement of the 1982 Embassy Grand Prix at Bristol on 5-6 June. Not only was it packed with action in all classes, but it featured the mammoth efforts of two men determined to show that ingenuity coupled with the will to win could succeed against tremendous odds. For BBC Grandstand viewers across Britain and audiences watching abroad, the compulsive action unfolding on the narrow 1.7-mile course was unlike anything seen in powerboat racing.

Seebold and his mechanic, Leo Molendijk, took on the leading giants of the sport and walked away with an armful of trophies. Although Seebold remained loyal to the Mercury marque of racing outboard, he had not been a works-supported driver since the company disbanded its racing team two years earlier. The two-litre V6 model was the largest unit available currently, and it was 1.5 litres smaller than those produced for OMC.

Seebold had equalled the lap times established by the 3.5-litre V8 Johnson and Evinrude outboards at the JPS World Formula I heat at Holme Pierrepont, Nottingham the previous year. But although he applied to race, he was unable to join the larger event because his Mercury was under the minimum capacity of 2,001cc. The Embassy Grand Prix was the opportunity he had been waiting for.

The challenge

As soon as the Bristol programme was approved, Molendijk began modifying a spare engine. He increased the capacity (probably by using a larger head gasket) by a mere five cubic centimetres, which was sufficient to comply with Formula I OZ rules. His only problem was that Seebold, who already had won the solid gold Duke of York Trophy three times and wanted it for a fourth, had only one boat available for both contests. This would necessitate changing the powerhead between heats.

Changing a powerhead in a hurry is difficult enough, but it is almost impossible in the 45 minutes available when the heats are spaced by a separate race. When one heat follows another, the feat is virtually impossible. But Molendijk did it in a little over nine minutes, and Seebold reaped a huge reward for his mechanic’s efforts.

Saturday’s drama

On Saturday, Billy gave a demonstration of his driving ability. For those who thought he won in the past because of his ‘special’ equipment, he left no doubt in anyone’s mind that driving is the key to success. At last, he was back with his OZ compatriots, and he loved every strenuous minute.

Seebold’s success in Formula I unlimited was achieved in spite of a 1,495cc engine capacity disadvantage, and his performance was such that he even lapped all other competitors using the 3.5-litre V8 Johnson and Evinrude racing outboards.

Italian Renato Molinari in his Martini-backed aluminium catamaran showed skill in a class of its own. He made all others, even Seebold, look decidedly slow. He won two of the three unlimited heats, but a loss of steering in the second race robbed him of the Formula I prize. Britain’s Tom Percival went on to win after Molinari’s retirement to gain a first day’s lead of 25 points over Seebold.

Tragedy strikes

The pattern was set to repeat itself in the second heats of Saturday, until tragedy struck in the last heat of the day. David Mason’s catamaran dug a sponson and flipped. What looked an unspectacular accident sadly ended in his death. This accident involved no other boat and, by its nature, could have happened on any race course. It was a blow when, after an almost accident-free day of racing, sombre and grieving competitors retired to their beds.

Mason had just come out of the left-hand bend on his approach to the pit turning marker when his boat lifted into the air and threw him clear. Unfortunately, Mason had repaired the hull himself after a similar flip at Bristol last year, and instead of a breakaway cockpit moulding, had fashioned his own version out of aluminium.

The reports of what actually happened were mixed. Some observers were certain he was thrown clear, and others said he was trapped in the cockpit. Mason suffered massive internal injuries and was dead on arrival at hospital despite the efforts of medical teams on the course.

Sunday’s triumph

By Sunday, the crowds poured in, and every time Billy Seebold swapped a motor and came out as either an ON or an OZ entrant, they went wild. When it came to the 25-lap Duke of York Trophy, the tension was almost too much to bear. Surely his equipment had had enough (and even Billy may have had enough). Yet he romped home.

The Duke of York Trophy race was stopped twice due to accidents. Nick Cripps’ outfit hooked and hit a wall, and John Hill ripped his starboard sponson off on the dock wall. When the race was finally completed, Billy Seebold had won the Duke of York Trophy for the fourth time, the first driver ever to achieve this feat.

While Billy collected his trophy, Leo was making the last change of motor. The OZs came out onto the pontoon, but there was no Seebold. And once again, we return to the beginning of this story, with the three-minute board raised and Seebold hurtling under the bridge at the last moment.

The final battle

With the three-minute board he appeared, and the crowds went totally mad. Molinari was not to be seen. The flag was dropped, and they were off for the start of the Embassy Gold Cup. Seebold got a roaring start and went straight into the lead with Roger Jenkins in second. By the fourth lap, Cees van der Velden, driving in a style reminiscent of past years, went into second place and appeared to be catching Seebold.

It was almost too much to watch, as they were only halfway through the race. Tom Percival had moved into third place, and as the noise of the potent machines rebounded on the dock walls, it was Seebold in the lead all the time. Seebold and van der Velden were both trimmed to maximum, and on occasion more than maximum, but as the laps came to an end, it was the American who had captured the heart of the spectators who took the chequered flag.

Van der Velden, who had driven hard, finished second, and Tom Percival took third place. The cheering continued, Leo fired champagne over everyone, the hierarchy of Imperial Tobacco looked happy, the press were everywhere, swamping this man from St Louis who seemed never to stop grinning.

The legacy

Seebold won the Duke of York Trophy (the first driver ever to win it four times) and the brand new Embassy Gold Cup. He also took the separate prize for the fastest lap (89.964mph). He would have taken the award for the separate three-heat two-litre ON event, but could not make up the one-minute, 28-second delayed starting time following one of these incredible engine changes.

Mercury were happy, and the Johnson and Evinrude drivers applauded in admiration. He was a driver who came to race, and race he did. Bristol is a tough course that requires the very best that a driver can offer. It tests every reflex and requires every ounce of concentration for every second on the course.

If you are really frightened out there, you shouldn’t be on the course. No one makes you race here, but I’ll be back next year.

Billy Seebold kept that promise. But within eight years, the Bristol Grand Prix would disappear from the racing calendar forever.

Why Bristol stopped

The 1982 Embassy Grand Prix was the 11th edition of what had become known as the Monaco of powerboat racing. From its inception in 1972, when Charlie Sheppard had the vision of racing powerboats in Bristol’s disused docks, the event had grown into circuit racing’s most prestigious and demanding venue. Up to 250,000 spectators would line the docks over race weekend, watching boats thunder through the narrow 1.7-mile course bordered by vertical stone harbour walls.

When Italian champion Renato Molinari first saw the course in 1972, he looked across the narrow stretch of water and asked organiser Charlie Sheppard: “We drive up that way?” When told they would return down the same side, Molinari paused before saying with a grin: “Is a little tight, yes? But OK.”

The danger was always present. The 1982 race was marred by the death of 41-year-old Dave Mason, who lost control of his catamaran during the last two-litre Formula II race on Saturday. Mason had repaired the hull himself after a similar flip at Bristol the previous year, fashioning his own cockpit moulding from aluminium instead of using a breakaway design. When his boat lifted into the air, the consequences were fatal.

But the event continued. Imperial Tobacco’s sponsorship as Embassy kept the Grand Prix alive through the 1980s, though there was a brief suspension in 1983 due to disputes over Formula 1 status. The race returned with various sponsors including Rolatruc, Mitsubishi and Technophone, maintaining its position as the most coveted prize in powerboat racing.

The end came on 17 June 1990. French driver François Salabert died when his boat hit the dock wall at 80mph during the Technophone Bristol Grand Prix. The 14 rescue boats, eight ambulances and 14 doctors on call could not save him. His death was to be the last at Bristol, but it proved to be the death of the event itself.

In the aftermath, organisers faced demands for additional safety features that would prove too costly to implement. More critically, no sponsor could be found to replace Technophone for the following years. The event that had drawn a quarter of a million spectators annually, had been broadcast on BBC Grandstand, and had attracted the world’s greatest powerboat racers simply ceased to exist.

Local hero Mike Zamperelli won that final 1990 race. The Duke of York Trophy, first presented in 1924 by King George VI and awarded at Bristol from 1977, was never contested again. The grandstands were dismantled. The docks returned to their commercial use. And powerboat racing lost its most spectacular and demanding venue.

Bristol City Council has shown little interest in commemorating the 19 years of racing history. As Roy Cooper from the charity Fast on Water noted when organising the Bristol 50 celebration in 2022: “To them, it’s as if the 19 years of the powerboat races never happened. If they are mentioned anywhere in articles on the history of Bristol Docks, it’s usually a short paragraph or sometimes only a sentence, or sometimes not mentioned at all.”

There have been occasional discussions about bringing powerboat racing back to Bristol, but nothing has materialised. The tight, twisting course that made Bristol the Monaco of powerboat racing also made it too dangerous and expensive to continue.

As long as there is circuit powerboat racing, those who witnessed Bristol will remember it. It was a tight course and a rough ride. With over 90 competitors, the world’s most exciting course, short snappy heats, and the kind of breathtaking tension provided that weekend in 1982 by Billy Seebold and his mechanic Leo Molendijk, the Embassy Grand Prix at Bristol remains the greatest show powerboat racing has ever produced.

Compiled from the original race reports by authors:

Ray Bulman reported on the sport of powerboat racing for six decades until his death in 2019.

Rosalind Nott was the editor of Powerboat & Waterskiing magazine and covered the sport with passion and insight. She lost her three-year battle with cancer in 2011.

John Moore’s involvement in powerboat racing began in 1981 when he competed in his first offshore powerboat race. After a career as a Financial Futures broker in the City of London, specialising in UK interest rate markets, he became actively involved in event organisation and powerboat racing journalism.

He served as Event Director for the Cowes–Torquay–Cowes races between 2010 and 2013. In 2016, he launched Powerboat Racing World, a digital platform providing global powerboat racing news and insights. The following year, he co-founded UKOPRA, helping to rejuvenate offshore racing in the United Kingdom. He sold Powerboat Racing World in late 2021 and remained actively involved with UKOPRA until 2025.

In 2025, he established Powerboat News, returning to independent journalism with a focus on neutral and comprehensive coverage of the sport.